On July 3, 2013. a military coup ousted the democratically elected government of Mohamed Morsi, putting an end to the Arab Spring.

Ten years after Egypt’s coup, Washington has yet to learn that authoritarian stability is an illusion. The role the United States played in the events leading up to the coup, and the coup itself, is still contentious, stated Shadi Hamid, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, in a piece published by Foreign Policy under the title, “Lessons for the Next Arab Spring”.

Muslim Brotherhood supporters blame the Obama administration for its unwillingness to stop the coup or even to call it one.

Coup supporters, meanwhile, claim that it was U.S. President Barack Obama who propelled the Brotherhood to power in the first place.

Among Western analysts and policymakers, the prevailing narrative is that the U.S. government was blindsided by the coup and, in any case, didn’t have the ability to do much about it.

However, drawing on journalistic accounts as well as more than 30 interviews I conducted with senior U.S. officials—including those who were in the room with Obama at key moments of decision—the available evidence points to a disturbing conclusion.

The conventional narrative that Obama was blindsided by the coup is simply false. The opposite is closer to the truth: Obama gave the Egyptian military what amounted to a green light to overthrow the country’s first-ever democratically elected government.

Democratization in the Arab world has long been hobbled by an “Islamist dilemma.” U.S. officials who might otherwise believe in democracy have found it more difficult to support in Arab countries because Islamist parties are the most likely to perform well and even win in free elections.

With Obama, there was some room for optimism. As the son of a Muslim father and the first U.S. president to have lived in a Muslim-majority country, Obama seemed more broadminded about Islamism than his predecessors. Yet this perceived openness also proved a liability. As one senior White House official put it to me: “Don’t forget, at the beginning, he’s accused of being an Islamist sympathizer himself. I think he had to fight that perception. And sometimes he overcompensated.”

This was a time when Obama’s very identity was being challenged. Remarkably, a majority of Republicans came to believe that Obama himself was “deep down” a Muslim.

But Obama was also a pragmatist who was temperamentally inclined toward care and caution. Stability was the watchword. And in the case of Egypt in the wake of the 2011 revolution, that meant supporting the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), Egypt’s transitional authority that took over in 2011 after former President Hosni Mubarak stepped down, even if it meant subverting the democratic aspirations of the Egyptian people.

The SCAF, Obama seemed to believe, would ensure that democracy didn’t get too out of hand. Obama admitted as much. “Our priority has to be stability and supporting the SCAF. Even if we get criticized,” he said. “I’m not interested in the crowd in Tahrir Square and Nick Kristof,” he added, referring to the New York Times columnist who had been critical of the administration’s Egypt policy.

In the interest of stability, the United States wanted the Egyptian military to hold presidential elections before parliamentary elections. As Dennis Ross, a senior advisor to Obama, described it: “Part of the reason that we had been pushing for presidential elections first was precisely because it was a given, at least to me, that in parliamentary elections, the Muslim Brotherhood would dominate.” Or, as U.S. Ambassador to Egypt Anne Patterson told me, “Our sort of default position was that [secular candidate] Amr Moussa was going to win [the presidency], which was an entirely Western way of looking at things.”

But parliamentary elections came first. In 2012, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party secured 43 percent of the seats in parliament, while Moussa was unable to advance past the initial round of voting for the presidency, garnering only 11 percent of the vote.

Morsi, who narrowly won the second round of presidential voting in June 2012, spent a turbulent year in office, culminating in mass protests against his government over deteriorating security and economic conditions. The vast majority of protesters weren’t calling for a military coup. They were calling for Morsi’s resignation or early elections. But the military, led by the enigmatic then-Defense Minister Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, seized the initiative and, within days, took power.

Memorably and awkwardly, weeks after the coup, State Department spokesperson Jen Psaki declared, “[W]e have determined that we do not have to make a determination about whether or not this was a coup.” A few weeks later, Secretary of State John Kerry commended Sisi for “restoring democracy”—a bizarre remark made all the more remarkable by the fact that it came after two separate massacres of Brotherhood supporters by the security services on July 8 and July 27.

Less well known, however, are the critical, tense days leading up to the coup, when disaster—and the killings still to come—might have been averted. These were days shrouded in mystery. This opaqueness offered the United States, after the fact, plausible deniability. Obama’s advisors could say they were caught off guard. The coup happened, it was a fait accompli, and they had to live with the world as it was, not as they wished it to be.

Within the U.S. government, there were some differences of opinion about Morsi and the Brotherhood. Due to institutional interests and proximity to Egypt’s generals, the Pentagon was more skeptical of Morsi, putting it in tension with the State Department and the White House, which were at least paying lip service to democracy. Senior defense officials such as James Mattis, who was commander of U.S. Central Command for part of Morsi’s tenure, tended to see democracy promotion as a luxury that distracted from counterterrorism. Mattis once described the Brotherhood and al Qaeda as “swimming in the same sea.”

Mattis found much to like in Sisi’s coup. As he put it: “What we basically saw was a popular impeachment with the largest crowds in modern world history out in the streets saying I’m done with this guy. Then we see the military muscle coming in and supporting the popular impeachment.”

Interestingly, Michael Flynn, who would rise to national fame as former President Donald Trump’s disgraced national security advisor, was the director of the Defense Intelligence Agency during the spring of Morsi’s fall.

“What we were going to see was a takeover of the country by the Muslim Brotherhood,” Flynn told journalist David Kirkpatrick in his recollections of the period. He visited Cairo that April, three months before Morsi was ousted. Egyptian generals saw Flynn as a kindred soul. They organized a “cultural day” for Flynn. Over lunch one day, Flynn and his Egyptian counterpart “scrawled out a map of the Islamist threats they saw around Egypt.”

While the State Department as a whole may have been better, Kerry was something of an outlier in Foggy Bottom, often provoking consternation among colleagues. As one senior advisor to Kerry told me, “He felt that [the coup] wasn’t a bad outcome for us from the standpoint of national security interests. He wasn’t a fan of the Muslim Brotherhood, big-time not a fan of Morsi.” Another State Department official put it more bluntly:

[Kerry hates Islamists. He hates them. I think it’s just that he’s somebody who is formed and shaped in another era of the world, and I think the way that he gained his knowledge and information about the Middle East was by talking to Arab leaders. And if you’re dealing with the leaders for however many decades in the Senate, you get a particular view. … Kerry likes dictators. It’s kinda like [President Joe] Biden. All these guys. They’re all from that generation of “just deal with strong men.” That’s all they ever knew in the Middle East.]In a conversation with Kirkpatrick, Kerry admitted to knowing Morsi was “cooked”—and that the military was readying itself to intervene—as early as March 2013, after he met with Sisi, then-defense minister, for the first time. After that meeting, Patterson warned the White House that “a coup was a high likelihood within a few months.”

In other words, in the days leading up to the coup, U.S. officials knew what was going on—and were in a position to try to block Sisi if they had wanted to. They did not try.

It is perhaps here that Washington’s Islamist dilemma became most evident. Reflecting on this period, Chuck Hagel, the defense secretary at the time, stated that he agreed with Saudi, Emirati, and Israeli claims that the Brotherhood was “dangerous” and had to be countered.

The first inadvertent green light for the military coup also happened to come from Hagel. Just days before the takeover, Hagel said to Sisi: “So I will never tell you how to run your government or run your country. … You do have to protect your security, protect your country.”

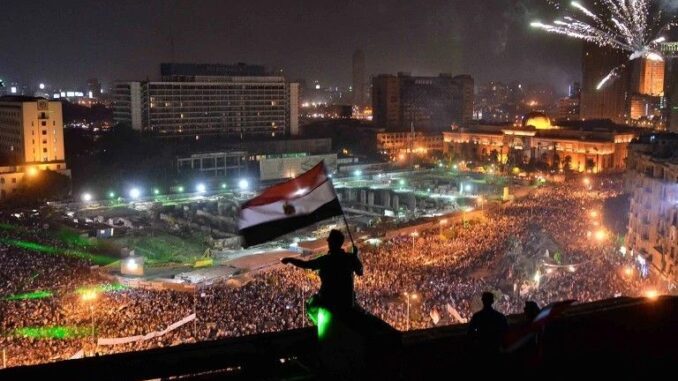

Hagel wasn’t the only one sending (mixed) messages to the Egyptian Army. On June 30, 2013, an estimated 1 million Egyptians took to the streets to protest Morsi’s rule. The military used the popular show of force to give Morsi a vague ultimatum: Satisfy protester demands within 48 hours, or the army would impose its own strategy to end the crisis.

But the coup hadn’t happened yet, and there was still time for Washington to clarify its intentions and preferences. Two days before the coup, on July 1, Obama called Morsi. Obama seemed to acquiesce, going so far as to rationalize what the army had done and what it was about to do. “The fact is, if the Egyptian military thinks the country’s stability is at risk, they are going to make their own decision,” he told Morsi, as reported in Kirkpatrick’s 2018 book, Into the Hands of the Soldiers. The military’s takeover was assumed as a given.

By July 2, a chaotic situation had only grown more so. Obama was traveling. His national security advisor, Susan Rice, was at the White House. Essam al-Haddad, Morsi’s national security advisor, called Rice from the presidential guard house in Cairo. Haddad was in a state of panic, alternating between fatalism and defiance. According to one White House official who was privy to the conversation:

[(Rice) gave an impassioned defense of democracy to this guy who was doing the same thing on the other end, saying that his fathers and forefathers had laid down their lives to try to protect Egyptian freedom and that he and Morsi were prepared to do the same thing. And that the only hope they had left was the United States. And she basically said, “We will not abandon you, we stand for democracy, we have made very clear.” …Obama wasn’t part of this conversation, but I assumed that she was reflecting his views. And she said, basically, “We will not let this stand, we will not let it.” … It was like over and over again. And I remember saying to her, “Susan, are you sure?” “Are we going to follow through on this?”]

On July 3, it was too late. By the time Americans woke up, Morsi had been detained in an undisclosed location. As the White House received updates, Obama gathered aides in the situation room. A difficult decision awaited. U.S. law prohibits the provision of aid to a government whose duly elected leader has been deposed in a “coup d’etat or decree in which the military plays a decisive role.” A White House advisor who was there walked me through how the conversation unfolded:

[I came in all hot and bothered, and so did a few others, that there was a clear letter of the law that said, “Declare the coup, cut off military assistance.” Actually, we weren’t even focused on the first thing, because only somebody who was purposefully obfuscating would say that it wasn’t a coup. …So, it was like, “When do we announce this?” That’s when I came in, expecting the conversation was going to be about that. And then Obama for the only time that I can recall in the years I worked for him, the only time, he came in and “cleared the debate.” He came in and said, “Well, so, we’re not going to declare this a coup, so what should we do?” I was totally taken aback by that, and so were many other people. And so it completely changed the tenor of the conversation.]

The administration’s public statements in the immediate aftermath of the army’s power grab reflected this approach: Obama said he was “deeply concerned by the decision of the Egyptian Armed Forces to remove President Morsi and suspend the Egyptian Constitution.” The word “coup” was noticeably absent.

Actors have agency. They make choices. For decades, Egypt was the second-largest recipient of U.S. military aid in the world behind Israel, having received tens of billions of dollars from Washington. There was no way the United States could have been neutral, however appealing the idea. But where exactly is the line between inaction and complicity?

When Obama finally started paying attention to Egypt after the army began moving against Morsi, he could have issued a warning to the generals. He chose not to. For his part, Sisi made his own calculations about what he could reasonably get away with. As it turns out, he deserves some credit. Sisi judged correctly that the United States would not stand in his way if he seized power. But what if senior U.S. officials had made different decisions when there was still time to make them?

At their first meeting in March 2012, what if Kerry told Sisi that a coup would be unequivocally opposed by the United States? What if Hagel had threatened an immediate aid cut if the army intervened? To put it differently, what if there was a policy against a coup before the coup?

Just blaming Kerry or Hagel is too easy and certainly too convenient. Hagel wasn’t authorized to employ either carrots or sticks. He might have been inarticulate and indulgent of Sisi, but it is unlikely that a different defense secretary would have fared much better. Any real effort to avert a coup would have required communicating to the Egyptian Armed Forces that a military takeover would trigger severe consequences.

It is difficult to imagine, but we can try: What if Obama had publicly announced prior to the June 30 protests that the United States would support the right of Egyptians to demonstrate peacefully but that any attempt by the military to use the protests for its own designs would be forcefully opposed? A full and immediate suspension of military assistance—including withholding spare parts, maintenance, and logistical support—would have grounded Egypt’s tanks and jets and other advanced weapons systems in a matter of weeks.

But perhaps that’s asking too much from an administration that was overextended in a region that it had always hoped to extricate itself from. I spoke to Patterson about how she remembered some of these critical moments. “The fact is, we probably did have leverage, but we were never going to use maximum leverage to prevent a coup.” When I asked her why, she said, “At that point, there were a lot of people that weren’t sorry to see Morsi go.”

It was a tragic coda for a tragic region. If only briefly, the Arab Spring held the promise that the United States could finally resolve its “democratic dilemma” in the Middle East. Washington’s reliance on Arab dictators was—and still is—justified in the name of stability. Yet it is difficult to look at the Middle East of recent decades and see anything resembling a “stable” region. The uprisings of 2011 were both a reminder and a confirmation that authoritarian stability is an illusion, if not an outright oxymoron. But some lessons are difficult to learn. If and when a second spring comes, U.S. officials will have to re-learn them all over again.