Russia’s war on Ukraine has adversely affected the Arab region, which heavily depends on wheat imports, including from these two countries.

The fallout from the war varies from country to country, but it has hurt one Arab nation more than the others: Egypt, states a report by Hilal Khashan published on Geopolitical Futures on 30 March 2022.

In Egypt, wheat shortages have further exacerbated supply issues precipitated by poor government planning and the country’s rapid population growth. For example, Egypt’s agricultural sector has been under pressure because of reduced flow from the Nile River as a result of the government’s mismanagement of the dispute over the Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

These problems have been compounded by inflation, which accelerated after the 2013 coup led by then Defense Minister Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Many expected the new political leadership to stabilize the country and relaunch the economy, but the situation only worsened.

In response to surging inflation, al-Sisi angered many Egyptians by urging them to refrain from buying expensive food items and to start losing weight. A revolt is inevitable, and it’s only a matter of time before a minor incident ignites a full-blown rebellion.

Volatile Issue

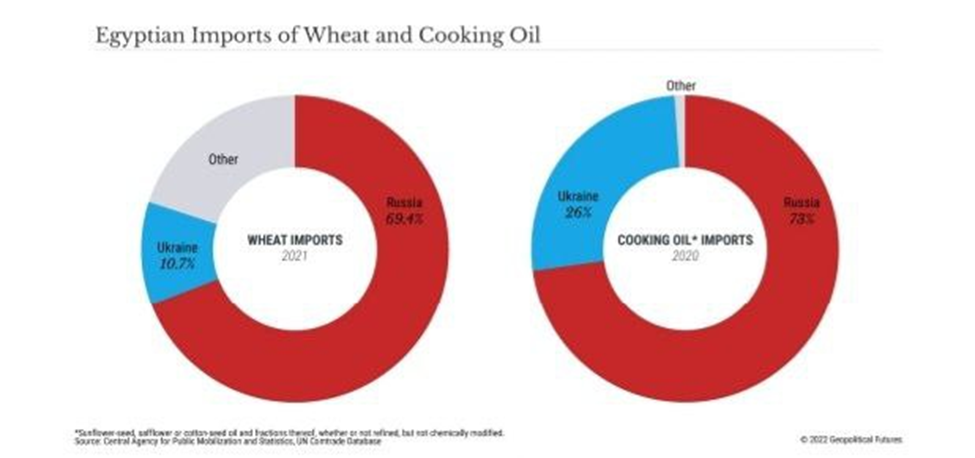

Bread – which in colloquial Egyptian Arabic translates as aish, literally meaning life – is more than just a staple food for most Egyptians. Egypt is the world’s largest wheat importer, with its domestic production covering only 50 percent of consumption. Moreover, at least 80 percent of Egypt’s wheat and cooking oil imports come from Russia and Ukraine.

Though there is no immediate food shortage, Egypt must now find new, more expensive providers from farther afield because of the disruption in supplies from two of its traditional sources. (It’s notable that the war has also affected the tourism sector, reducing the flow of travelers into Egypt from Russia and Ukraine. The loss of revenues from tourism and the sudden flight of foreign investment makes it extremely difficult for the government to meet its financial obligations.)

Since the war began last month, food prices have increased 25-50 percent and are likely to keep rising. But al-Sisi has responded to the problem with insensitive remarks, imploring the Egyptian people to pray to God for relief, thus leaving their welfare and survival up to divine intervention. Some on social media have lamented Sisi’s reaction.

Food supplies and prices have historically been a volatile issue in Egypt. Attempts by previous governments to reduce bread subsidies resulted in massive public protests. In 1977, President Anwar Sadat decided to slash subsidies on staple food items, causing violent riots that he blamed on Egyptian communists.

Despite the International Monetary Fund’s insistence on curtailing subsidies, Sadat reinstated them, deeming that his political survival was more important than financial reform. During the 2011 uprising, Egyptian demonstrators chanted “bread, freedom and social justice.”

When the government considered cutting bread subsidies in 2017, protests erupted again. Demonstrators blocked traffic and were undeterred by the deployment of the army. Al-Sisi responded by ordering the immediate issuance of temporary bread ration cards to defuse the crisis.

Last week, al-Sisi announced that Egypt’s Solidarity and Dignity Program would secure around $7 billion to mitigate the consequences of the international food and energy crisis. But the funds are unlikely to make much difference in a country with more than 100 million people, where malnutrition is responsible for more than 65 percent of child mortality. Egypt, after all, is one of three dozen countries that account for 90 percent of the world’s malnutrition.

Economic and Political Condition

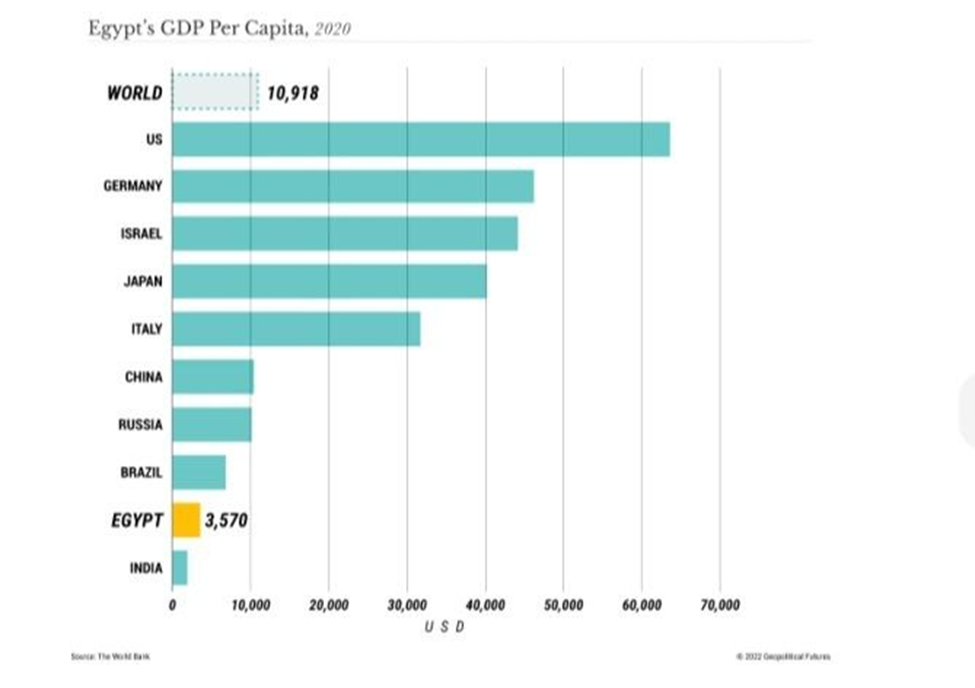

Moreover, the food issue needs to be examined against the backdrop of Egypt’s economic and political decline. With a per capita income estimated at $3,570, compared to the world average of $11,000, Egypt is an economically underdeveloped country. The Egyptian economy does not run according to economic principles but instead according to al-Sisi’s whims.

The Central Bank recently devalued the Egyptian pound by 17 percent to the dollar. It also raised the interest rate by 1 percent in response to rising inflation as the government sought an $8 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund. Al-Sisi doesn’t show a genuine desire to establish inclusive and sustainable economic growth. Corruption, nepotism, and consolidation of the public sector’s share of the market are driving the competition out of business.

After investing in megaprojects such as the new administrative capital and impressive palaces under al-Sisi’s administration, the government is also severely in debt. When al-Sisi staged the coup in 2013, Egypt’s public debt was less than $17 billion. Last year, it reached a record high of $138 billion. Servicing this debt equals three times the combined revenue accrued from the Suez Canal and tourism.

The United Arab Emirates has taken advantage of Cairo’s financial difficulties. It has acquired substantial business assets in Egypt, with its investments now exceeding $6 billion. Roughly 1,200 UAE companies are already active in Egypt, and Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund aims to buy the Egyptian government’s shares in several firms, including the International Commercial Bank, for $2 billion. The UAE also dominates Egypt’s arts, film and media industries.

Under al-Sisi’s management, authoritarianism has also been on the rise in Egypt. The country at least had the pretense of democracy under former President Hosni Mubarak. Egyptians tolerated his despotic rule until he began grooming his son to succeed him. Al-Sisi, however, doesn’t hide behind a veneer of democracy.

He brutally eliminated the opposition and even oppressed officials, party leaders, activists and army officers who backed his 2013 coup to overthrow Mohammad Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected civilian president. When he took power, he tried to charm the Egyptian people by telling them: “Do you not know that you are the light of my eyes?” But he lacked the charisma of former Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and became a tyrant instead.

Al-Sisi depoliticized and suppressed Egyptian civil society, either jailing its leaders or driving them to seek asylum abroad. He brands anyone who disagrees with him a foreign agent threatening the fabric of the nation. He also doesn’t trust the people around him.

In the tradition of other Arab presidents, Sisi is grooming his son, Mahmoud, to play a crucial role in Egyptian politics and eventually succeed him. He recently promoted him to deputy head of Egyptian general intelligence and put him in charge of Egyptian relations with Israel. Al-Sisi’s son is involved in secret talks with the Israelis to create an industrial city in northern Sinai as part of a plan to resettle Palestinians. Considering the declining quality of life in Egypt, his authoritarianism could accelerate attempts to oust him.

Pushed to Revolt

So where is this situation leading? For years, the common perception was that most Egyptians were politically passive because they felt powerless. Even informed and educated people won the reputation as being members of the “couch party,” an Egyptian term referring to the silent majority. The 2011 uprising, however, debunked the claim that the masses will not rebel.

Al-Sisi has appeared insensitive to Egyptians’ concerns about rising food prices, suggesting they purchase less expensive food. He also invested billions in palaces and a new administrative capital, and purchased expensive military hardware, including two helicopter carriers and Rafale fighter jets, even though Egypt hasn’t gotten involved in foreign conflicts, not even to defend its claims to the Nile River.

Al-Sisi therefore shouldn’t feel secure about his political position. The army – which was historically very popular among Egyptians, though its support has been waning of late – doesn’t support the establishment of dynasties, including the one Mubarak tried to hand over to his son. Given its disapproval of al-Sisi’s erratic economic and regional policies, it’s unlikely he will remain in power long enough to see his own son succeed him.

Al-Sisi lost the military’s support in part because he eliminated the ranking officers who backed his coup against Morsi and in part because the military did not want to associate with a ruler who failed to deliver on his promises to the people. It was a professional army until Mubarak and al-Sisi used bribery to curry favor within its ranks. Its second tier officers are politically disinclined and elicit a sense that al-Sisi will be Egypt’s last military ruler.

Arab satellite TV stations have devoted round-the-clock coverage to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, describing it as a war between the forces of democracy and authoritarianism. With the Russian army’s failures there, Arabs suddenly woke up to the reality that dictatorships are inherently weak despite their impressive array of munitions.

U.S. President Joe Biden said, “the world’s democracies must prepare for a long fight against autocracy.” As the conflict unfolds, his strong words will echo in the Arab region. One would expect Egypt – the most populous Arab country with a brief, if unstable, democratic interlude in 2011-12 – to lead the second phase of the Arab uprisings.

One potential spark for such a revolt is the recent protests at the Maspero Television Building, the headquarters of the Egyptian Radio and Television Union, over a decision to scale down operations, lay off several thousand employees, slash salaries and reduce benefits.

The state-controlled union was generally supportive of al-Sisi’s government, defending his policies, defaming his critics, and legitimizing his regime after the coup. So far, security forces have not suppressed the protests. Should they spread to Cairo, however, the police will crush the unrest with a force that could ignite a new uprising.

The Arab region is often described as a volcano ready to erupt. Egypt, the Arab region’s historical pacesetter, will likely be the site of the first eruption thanks to its population and its heavy cultural, literary and political influences.