Several prominent Egyptian figures have announced they would stop sharing their views publicly due to the prevailing political climate, belying Sisi’s claims about openness toward alternative viewpoints.

Over last week, several Egyptian public figures announced that they would not share their views in public, due to the political climate prevailing in the country these days, which belies Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s most recent claims that his regime is open toward alternative viewpoints.

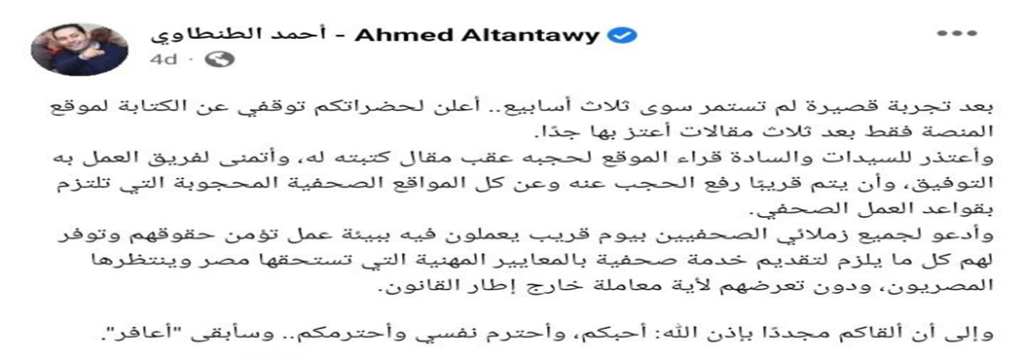

On August 5, Journalist Ahmed Tantawi revealed that he would stop writing for al-Manassa after one of his three articles led authorities to block the news website in July.

Tantawi expressed his wish that “the ban on al-Manassa and all the blocked news sites that adhere to the rules of journalistic work will soon be lifted,” a wish that echoed dozens of civil society organizations in a joint statement signed about a week ago.

Tantawi resigned as president of the Karama Party last month after disagreement within the party, and within the larger Civil Democratic Movement, about whether to withdraw from al-Sisi’s national dialogue over the slow pace of political prisoner releases.

Members of civil society have also called on authorities to lift the bans on news websites ahead of the dialogue to demonstrate that they are serious about reform.

Tantawi added, “I pray for my fellow journalists that they can soon work in an environment that secures their rights and provides them with everything necessary to present a journalistic service at the professional standards that Egypt deserves and is waiting for, without being subjected to any treatment outside the framework of the law.”

Two days earlier, Cairo University political science professor and prominent intellectual Hassan Nafaa tweeted that he was regretfully shutting his Twitter account “for reasons beyond my control.”

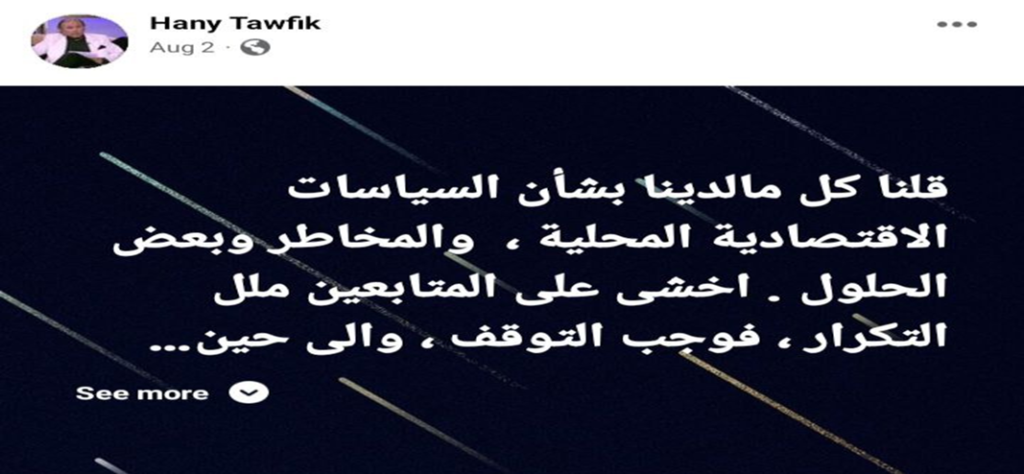

Also, economic commentator Hany Tawfik said that, in order to stop repeating the same advice, he would halt his public economic analyses “until new variables emerge, justifying a return to writing on these matters.”

Over the past year, Egypt’s Abdel Fattah al-Sisi tightened his unilateral grip on power and maintained his brutal repression, perpetuating a human rights crisis that is deeply destabilizing for the country.

“The Egyptian government has committed a staggering number of gross human rights violations, including extrajudicial killings, forced disappearances, torture, life-threatening prison conditions, arbitrary and political detentions, transnational repression, widespread media censorship, and significant restrictions on the right to free expression, assembly, and association,” stated the US State Department’s annual Country Reports on Human Rights Practices.

Al-Sisi also expanded his own power through the rubber-stamp parliament, permanently codifying provisions of the state of emergency, and he continues to target and constrain human rights defenders and civil society activists despite his government proclaiming this the “Year of Civil Society.”

In an attempt to whitewash these abuses on the global stage—similar to the Egyptian cabinet’s creation of a Supreme Standing Committee for Human Rights in 2018—the Egyptian government has launched a number of initiatives such as issuing a National Strategy for Human Rights, reestablishing the Presidential Pardon Committee, and most recently announcing a National Dialogue.

While these efforts have been accompanied by some political prisoners being released, more have been arrested or had their pretrial detentions renewed than have been released since April 2022, and thousands more remain in detention.