Egypt says Ethiopia has “summarily rejected” its plan for key aspects of operating a giant dam the East African nation is building on the Nile, while dismissing Ethiopia’s own proposal as “unfair and inequitable”.

The comments in a note circulated to diplomats last week show the gap between the two countries on a project seen as an existential threat by Egypt, which gets around 90% of its fresh water from the Nile.

The note distributed by the Egyptian foreign ministry, a copy of which was seen by Reuters, points to key differences over the annual flow of water that should be guaranteed to Egypt and how to manage flows during droughts.

It comes as Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan met on Sunday and Monday for their first talks over the hydroelectric dam in more than a year. A spokesperson at Ethiopia’s foreign ministry, Nebiat Getachew, said that the meeting had so far produced no agreements or disagreements and gave no immediate response to the Egyptian claims.

Egyptian officials were not immediately available for comment, but Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry has expressed unease in recent days over delays in negotiations.

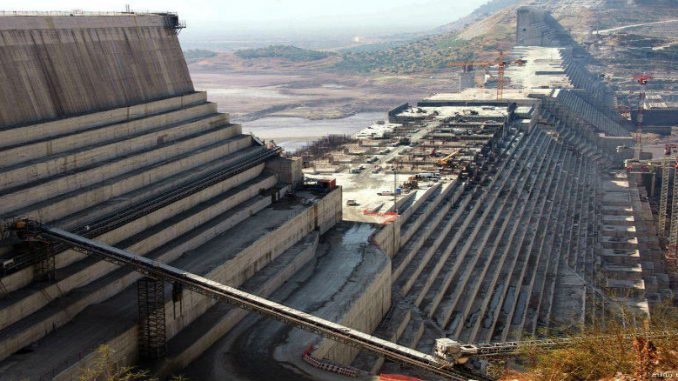

The $4 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) was announced in 2011 and is designed to be the centrepiece of Ethiopia’s bid to become Africa’s biggest power exporter, generating more than 6,000 megawatts.

In January, Ethiopia’s water and energy minister said that following construction delays, the dam would start production by the end of 2020 and be fully operational by 2022.

The dam promises economic benefits for Ethiopia and Sudan, but Egypt fears it will restrict already stretched supplies from the Nile, which it uses for drinking water, agriculture and industry.

DEADLOCK

Though nationalist, sometimes belligerent rhetoric between Egypt and Ethiopia has cooled in recent years, the sides have remained deadlocked.

A report from International Crisis Group earlier this year warned that Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan could “blunder into a crisis if they do not strike a bargain before the GERD begins operation”.

Egypt says it shared its proposal for filling and operating the dam with Ethiopia and Sudan on July 31 and Aug. 1, inviting both countries for a meeting of foreign and water ministers.

“Unfortunately, in a letter dated August 12, 2019, Ethiopia summarily rejected Egypt’s proposal and declined to attend the six-party meeting,” the Egyptian government’s note said.

Ethiopia had instead proposed a meeting of water ministers to discuss a document that included an Ethiopian proposal from 2018, it said.

Both proposals agree that the first of five phases for filling the dam should take two years, at the end of which the GERD’s reservoir in Ethiopia would be filled to 595 metres and all the dam’s hydropower turbines would become operational.

But the Egyptian proposal says that if this first phase coincides with an extreme drought on Ethiopia’s Blue Nile, similar to that experienced in 1979-1980, then the two-year period should be extended to keep the water level at Egypt’s High Aswan Dam from dropping below 165 metres.

Without such a concession, Egypt says it would risk losing more than one million jobs and $1.8 billion in economic output annually, as well as electricity valued at $300 million.

After the first stage of filling, Egypt’s proposal requires a minimum annual release of 40 billion cubic metres of water from the GERD, while Ethiopia suggests 35 cm, according to the Egyptian document.

The note cites Ethiopia as saying last month that Egypt’s proposal “put(s) the dam filling in an impossible condition”, a charge Egypt dismisses.

“The Ethiopian proposal … overwhelmingly favours Ethiopia and is extremely prejudicial to the interests of downstream states,” it says.