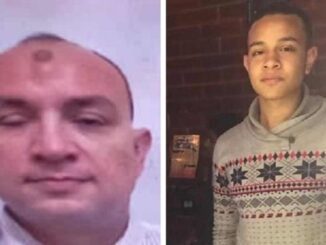

At the Nour Mosque in Abbasiya Square, in the heart of Cairo, the crowd were gathered waiting for detained blogger Shady Abu Zeid to attend his father’s funeral. The family of 25-year-old satirist and video blogger Shady Abu Zeid, along with a number of his friends, were gathered for funeral prayers for Shady’s father. Hassan Abu Zeid had died on Saturday evening, after a severe deterioration in his health over the past few months.

Funeral Postponed Waiting for Shady

The funeral prayers had been postponed for a few hours in the hope that Shady — who had been imprisoned since May 2018 — would be allowed to come and say goodbye to his father. On Sunday, the Supreme State Security Prosecution had agreed to grant him a temporary release so that he could attend his father’s burial that day.

The move came as a surprise — similar requests made by detainees to attend their relatives’ funerals are often rejected, or see release procedures stall for so long that the funeral proceedings are over before the jailed relatives arrive. Shady’s family had petitioned for him to be able to visit his father in intensive care, a request that had been summarily rejected.

The Satirical Blogger and Vague Charges

A satirical video blogger, Shady is a comedian of slight build and strong presence. Last May, security forces raided his home with little warning. They searched his house, confiscated some of his belongings and arrested him.

Ever since, he has been held in remand detention on vague charges, however, they have been the common charges raised under al-Sisi’s rule. He was charged by joining a terrorist organization and spreading false news.

He was added to Case 621/2018, known to be a case that non-Islamist defendants are added in order to silence them. Defendants currently include bloggers Mohamed Ibrahim (Oxygen) and Mohamed Khaled, as well as activists like Shady al-Ghazali Harb amd Amal Fathy and Sherif al-Rouby.

In less than half an hour, the funeral prayers at the mosque were over, but Shady had not arrived. His father was carried out in a casket on people’s shoulders and placed in an undertaker’s van to head to the family burial plot in Bab al-Nasr, in Cairo’s Gamaleya district. Everyone hurried after the van, racing through a bitterly cold dust storm that seemed to reflect the cruelty of the situation: An imprisoned son, a father who had left before he could see him free and a family uncertain about whether their loved one would be able to make it in time to say a final goodbye.

At the burial plot, family and friends reconvened and the crowd had grown to be larger than the one at the mosque. All eyes were fixated on the road leading to the burial plot, as people swapped unconfirmed bits of information regarding Shady’s whereabouts. To kill time and the anxiety of waiting, some began discussing how best to receive Shady when he arrived: “We shouldn’t gather around him so as not to provoke security.””We should give him a moment ‘alone’ with his father.””He might not make it — many other prisoners weren’t allowed to leave.”

By time, people lost hope and began to believe that Shady wouldn’t show up. “Perhaps they’ll let him out tomorrow instead to receive condolences.”The sheikhs present began reciting burial prayers. Shady’s father was about to be lowered into the burial chamber when, suddenly, there was news — seemingly more sure of itself, this time — that Shady was on his way. Again, they decided to wait.

Another Two hours

It was a two-hour wait for everyone, including the grieving elderly, all of us standing in the midst of the growing cold and dust. Everyone continued staring at the road expectantly, while Shady’s father’s body waited in its casket.

As the sun began to set and darkness approached, a police sergeant emerged. He examined the road to the graveyard to figure out a “safe passage” for Shady’s arrival.

Security personnel — a force that included officers from the State Security Investigations Services, the Cairo Security Directorate and the local police station — then appeared.

Shady emerged through what seemed like a back entrance to the burial plot. Wearing his prison uniform — a light, white tracksuit — he made his way to the front, surrounded by many guards and with his hands in shackles.

The Last Goodbye under Surveilling Security

Family members led him to the casket. There, he was permitted a few minutes to say goodbye, under the watchful eyes of the surveilling security detail.

The casket was finally lowered into the ground, amid increasingly loud sobs. Family and friends negotiated with the officers to allow Shady to receive a few quick condolences from people present. Shady was permitted to stand by the side of the road, surrounded by guards who grudgingly allowed his sister, mother and a few other family members to stand next to him. Shady was being held by security personnel as he stands to receive condolences.

Quicker than it had begun, the moment was over, and it felt as though there could have been little solace for Shady as he received a few hurried condolences before being escorted back to his prison cell.

This month, in an interview with Scott Pelley on 60 Minutes, the Egyptian government later asked not to be shown, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi denied jailing his opponents to maintain his regime and the massacre of 800 civilians by Egypt when he was Defense Minister.

Al-Sisi became the country’s Minister of Defense when Mohammad Morsi became the country’s first democratically elected president after the Arab Spring revolts.

A year later, President Morsi was ousted in a military coup by al-Sisi on live TV. As then-Minister of Defense, al-Sisi is blamed for the 2013 massacre of nearly 1,000 supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood who protested the coup.

Human Rights Watch estimates al-Sisi, a former army general, is holding 60,000 political prisoners. “I don’t know where they got that figure. I said there are no political prisoners in Egypt. Whenever there is a minority trying to impose their extremist ideology we have to intervene regardless of their numbers.”

The U.S. State Department says killings and torture are carried out in al-Sisi’s prisons today, just as they were before he took power.

Critics say al-Sisi became even more autocratic than any of his predecessors in Egypt’s modern day history.

Pelley speaks with a former prisoner who was jailed for reporting false news while taking pictures of the 2013 massacre. Mohamed Soltan, an American citizen, recalls, “I was targeted because I had a camera. I had a phone and I was tweeting.”

After almost two years in prison, the Obama Administration secured his release. Soltan says they used sleep deprivation and isolation to torture him. A strobe light was used to make him convulse. “Guards that were assigned to me…would pass razors under the doorstep and the officer doctors would say to me, ‘Cut vertically, not horizontally so you can end it fast.”