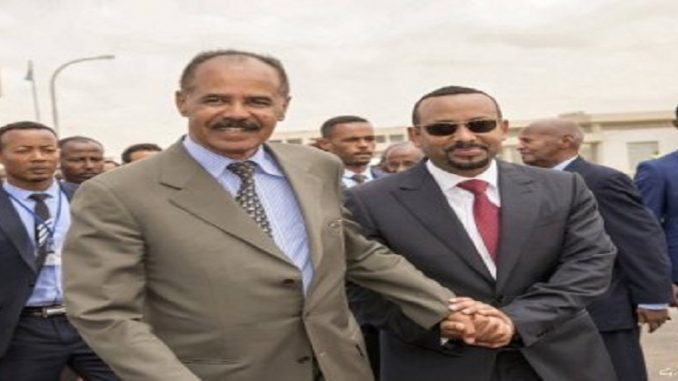

There have been numerous changes in local and regional politics since the election of Abiy Ahmed into the office of Prime Minister of Ethiopia. Notable is the recent peace agreement reached between Ethiopia and Eritrea sparking much optimism for future relations in the Horn of Africa.

The recent

peace deal between Ethiopia and Eritrea, signed 16 September 2018, is set to have lasting consequences for both countries and for the Horn of Africa as a whole. The agreement was reached soon after Abiy Ahmed was confirmed as prime minister of Ethiopia in April. Many regional changes have occurred in the five months since his election: Eritrea re-established ties with Somalia in July; thousands of political prisoners were released in Ethiopia and Eritrea; and Djibouti and Eritrea concluded a peace agreement regarding the dispute around Doumeira. The changes are likely to continue, spurring regional integration and revitalising the regional organisation, Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD). A worrying factor, however, is the role of outside powers in the negotiations, especially with Eritrea’s strategic location along the Red Sea in a sea lane that certain Persian Gulf states seek to control.

History

Eritrea was annexed to Ethiopia to form part of a federation at the end of

British colonisation between 1941 and 1952. Before this, Eritrea had been an Italian colony, from around 1869. Ethiopia had eluded European rule except for a brief period between 1936 and 1941 when it was absorbed into Italian East Africa (incorporating Eritrea and Italian Somaliland). There are nine

major ethnic groups in Eritrea: the Tigray- and Tigre-speaking groups include the Mensa and Marya; the other seven groups include the Afar, Bilen, Beni Amir, Kunama, Nera, Rasha’ida and Saho. Eritrean and Ethiopian liberation movements, chiefly the Eritrean and Tigrayan liberation fronts, which emerged during the 1960s, were partners in the fight against Emperor Haile Selassie, who had facilitated Eritrea’s annexation. After Selassie’s ousting in 1974, the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police and Territorial Army (or ‘Derg’), led by Major Mengistu Haile Mariam, controlled the Ethiopian government until 1977. At the time, the core of these liberation movements was opposition to the centralisation of power in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital. In Ethiopia, Tigrayans (under the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF)) sought control of a strip of territory in the north of Ethiopia, incorporating the homeland of Aksum, while the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) initially sought more control of the territories now known as Eritrea.

The cooperation between the TPLF and EPLF masked ideological and strategic differences between them. Italian colonisation of Red Sea territories, including the Eritrean capital Asmara, had concretised an independence tendency within the EPLF, a Communist movement that wanted to align with the Soviet Union. The TPLF was Maoist and was critical of Russian support for the Derg. By the 1980s, the TPLF had gained control of Tigrayan territory and sought to extend it toward Addis Ababa, while the EPLF aimed to maintain and consolidate control over Asmara. Although the two groups did not agree on where the border between their respective claimed territories should lie, they agreed to postpone border demarcation negotiations until after the Derg was overthrown and to continue cooperation in the meanwhile.

The TPLF also entered into a partnership with Oromo and Amhara groups opposed to the Derg and together formed the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), which took control of the country in 1991. This was partly as a result of the collapse of the Soviet Union, which had trained and funded the Derg. The EPLF declared independence for Eritrea in 1993 and was supported in this by the EPRDF under Meles Zenawi. Trade between the

two countries was largely unhindered and two-thirds of the imports of land-locked Ethiopia traversed through the Eritrean ports of Assab and Massawa.

Roots of the recent conflict

In May 1998, a two-year border war was fought between Ethiopia and Eritrea over the town of Badme, claimed by Eritrea but occupied by Ethiopia. Between 10 000 and 50, 000 deaths resulted from the war. The

Algiers Accord, mediated by the then Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 2000, partially halted the conflict, but Ethiopia rejected a 2002 ruling by a border commission, instituted by the OAU, that declared Badme to be Eritrean. Eritrea subsequently hosted Ethiopian opposition movements, including the Marxist Ginbot 7 group, while Ethiopia’s strategy included ensuring having Asmara expelled from IGAD and a UN arms’ embargo on Eritrea. Both countries, however, refrained from direct clashes, and the border remained relatively quiet. A 2016 skirmish threatened a return to war, but the ‘No Peace, No War’ status was maintained.

The conflict also played out regionally, with the two governments funding proxies. Thus, while Ethiopia intervened in 2006 to assist the US-supported Transitional Federal Government of Somalia against the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), Eritrea dispatched soldiers to assist the ICU and arm its more militant component (whose successor was al-Shabab). The conflict between the two states also had negative domestic consequences, resulting in increased repression. Eritrea’s President Isaias Afwerki, for example, used the conflict to justify his policy of indefinite conscription, while Ethiopia used accusations of Eritrean links to justify its crackdown on the opposition.

Roots of the rapprochement

The resignation in February 2018 of Hailemariam Desalegn Boshe from his position as prime minister created space for resuming talks between the two states. His relatively-young successor, Abiy Ahmed (41), used diplomacy with Eritrea as an opportunity to shore up political legitimacy and released thousands of political prisoners.

Significantly, Ahmed is from the country’s Oromo ethnic group that, although comprising a majority, was largely shunned from governance by the minority Tigrayan (who make up six per cent of the population). Ahmed’s ascension to power thus ended the two-year long Oromo protests, which had threatened to split the EPRDF. Ahmed also began peace talks with another Ethiopian opposition group, the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), lifting its designation as a terrorist group and freeing its leadership and the leadership of Ginbot 7. Another Oromo group, the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) was also removed from the terrorist list and it subsequently signed a ceasefire agreement with Addis Ababa. In August, Ahmed deployed the Ethiopian army to the country’s eastern Somali region, where the ethnic Somali ONLF is active, in order to end abuses by the paramilitary Liyu Police (which had been established to crush the ONLF). The president also weakened the powers of the TPLF and his own Oromo Democratic Party (ODP) by restructuring the party while retaining its leadership. He is seemingly less concerned about the dispute with Eritrea over Badme than the Tigrayan and Amhara have been, thus ensuring that he is not hamstrung by their sympathies for the region.

These measures have enabled Ahmed to begin peace talks with Asmara. He used Afwerki’s May visit to Saudi Arabia to request the Saudis to facilitate direct communication between himself and Afwerki. Although initially unsuccessful, this offering – coupled with Ahmed’s assertion that Ethiopia would abide by the 2002 OAU border commission ruling on Badme – resulted in the 8 July and subsequent 16 September deals.

Emirati and Saudi roles

The involvement

of Saudi Arabia and UAE was an important element contributing to the deal. Both Ahmed and Afwerki credited them with having had a crucial role in the success of negotiations. Afwerki visited the UAE twice in July, before and after the signing of the 8 July agreement; Ahmed visited Saudi Arabia in May and July, in his first visit outside Africa since he took power in April. This led to the 16 September deal being signed in Saudi Arabia.

Abu Dhabi had offered Asmara a large aid and security package if it signed the agreement; the UAE subsequently announced over three billion dollars in aid to Ethiopia, and the Emirati crown prince, Mohammed bin Zayed, visited the country in June.

At the heart of the UAE’s interest is its objective to control

the sea lanes around the Horn of Africa through the creation of naval bases. It aims to manage port traffic as a projection of its power in the Horn and an attempt to undermine Iranian activities in the region. The Emiratis have port and basing agreements in Berbera (Somaliland), Bosaso (Somalia), Assab (Eritrea), Mukalla, Aden and Mocha (Yemen).

Consequences of détente

The détente will bring much-needed change within both Ethiopia and Eritrea. Telephone systems between the countries have been reconnected and families are able to meet after decades apart. Trade is set to recommence, and Eritrea will benefit from Ethiopia’s rapid economic growth, which will be made easier by Eritrea’s decision to again use the Ethiopian currency, the Birr. Ethiopian Airlines has already announced it will purchase around twenty per cent of shares in Eritrea’s national carrier, Eritrean Airlines. Eritrea’s ending of repeated military conscription will allow its citizens to live more normal lives and will likely reduce the number of Eritreans fleeing the country. Currently, Eritrea has one of the largest refugee populations attempting to escape the continent, mainly as a result of the military conscription.

Of course, with such delicate processes, not all will efforts will proceed smoothly. Some residents of Badme, for example, oppose their new designation as Eritrean. Furthermore, there appears to be discontent among Ethiopia’s Tigrayans who had previously benefited under Zenawi and Desalegn. Tigrayans could mobilise against their reduced political influence. Hardliners have expressed opposition to Ahmed’s policies and may again appeal to Tigrayan ethnicity, which becomes particularly concerning when one considers that many Tigrayans hold influential positions in the country’s army and security apparatus.

Within Eritrea, increased economic opportunities may result in a loosening of Afwerki’s grip on the country, which could have unpredictable consequences. These could potentially open up the political situation or worsen it – if the president seeks to maintain tight control. Providing employment opportunities for the tens of thousands of former conscripts will be imperative. There are also logistical difficulties that can be expected, such as those related to the currency changeover and migration. Little is known too about how the Ethiopian government will deal with hundreds of thousands of Eritrean refugees it hosts.

The détente will also have lasting consequences for the region. Eritrea has already re-established

diplomatic ties with Somalia after a fifteen-year break, and Somalia has called for the suspension of sanctions and the arms’ embargo on Eritrea. Furthermore, Ahmed’s negotiations with the ONLF will reduce the need for Ethiopia’s presence in Somalia. It is noteworthy that Ethiopia’s 2006 intervention was

partially informed by its fear that disillusioned Ogaden people might appeal to the ICU and use Somalia as a rear base to mount attacks in the Ogaden area.

At the same time, the relative stability within Ethiopia and on its borders will allow the regime to replenish its troops in the multilateral and multinational AU-UN mission in Somalia (AMISOM). Addis Ababa has already signed onto a communique, issued by the five troop-contributing states – Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Burundi and Djibouti – in March 2018, calling for an extension of the 21 500-strong force. This is a vastly different strategy when compared to Addis Ababa’s previous unilateral intervention which was intended to secure Ethiopian interests in Somalia and to ensure the endurance of conflict in the country in support of US-backed warlords.

In an attempt to reduce tensions with Somalia, Ahmed visited that country’s president, Mohamed Abdullahi ‘Farmajo’ Mohamed, in June. After their meeting, the two leaders issued a joint statement that pledged their cooperation on a number of issues, including the development of four Somali ports, infrastructure (including roads linking the two countries), and expanding visa services to promote cultural exchanges.

The Ethiopia-Eritrea deal also encouraged a 6 September peace agreement between Djibouti and Eritrea over the Doumeira mountain and islands. Although details of the deal are scant, it ends a ten-year conflict between the two countries that had threatened to rupture following the withdrawal of Qatari peacekeepers in 2017. Ethiopia and Somalia played critical roles in mediating the negotiations, which were concluded in Djibouti. Riyadh also played a significant role in forcing both parties to the table, in the interests of protecting its base in Djibouti.

Working through IGAD, Ahmed leveraged Ethiopia’s newfound influence to mediate a

peace agreement between the two main rival South Sudanese groups, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and its breakaway faction, the SPLM In Opposition (SPLM-IO). Signed on 12 September in Addis Ababa, the agreement is similar to the failed December 2015 power-sharing agreement between the SPLM’s Salva Kiir and SPLM-IO’s Riek Machar.

Yet, not all states in the region are thrilled about the Eritrea-Ethiopia rapprochement. Djibouti stands to lose the most because of Ethiopia’s port diversification. This is aggravated by Ethiopia’s comparably larger economy and almost double-digit rate of economic growth. Currently, over ninety per cent of Ethiopian trade passes through Djibouti’s Doraleh port. Djibouti had previously taken this for granted, leveraging Doraleh’s current and future revenue as collateral for many long-term loans for infrastructure development. A reduction in revenue from Doraleh as Ethiopia begins using Somali or Eritrean ports will thus reduce the Djibouti government’s ability to meet its debt commitments.

Conclusion

The Ethiopia-Eritrea peace agreement may have long-lasting consequences in both countries and within the Horn region. It is likely to spur on regional integration, especially as Ethiopia diversifies its shipping routes. Its strategic location will ensure that Eritrea’s ports remain relevant, with Ethiopian support, for Gulf-African and Indian Ocean trade. The agreement could also re-energise IGAD, particularly if Ethiopia plays a bigger economic role in the region. Eritrea’s re-accession to IGAD and its re-establishment of diplomatic ties with Somalia – which are direct consequences of the deal – could assist in finding a solution to the current Somali crisis that has destabilised much of the Horn in the past ten years. Ethiopia and Eritrea will now have less interest in supporting proxies in the conflict, which was a key factor in the conflict’s perpetuation.

The roles of the UAE and Saudi Arabia in influencing the deal may be a matter of concern, given their aspirations to control strategic Horn ports and establish bases there. Some of these positions have already been used for their attacks on Yemen and to enforce the blockade on Qatar. Additionally, these ports have assisted fragmentation of some states in the region, with UAE and Saudi funding, thus empowering groups with secessionist aspirations. This has been the case in Somalia and Yemen, where UAE port and base construction has rendered it almost impossible for these countries to remain unified