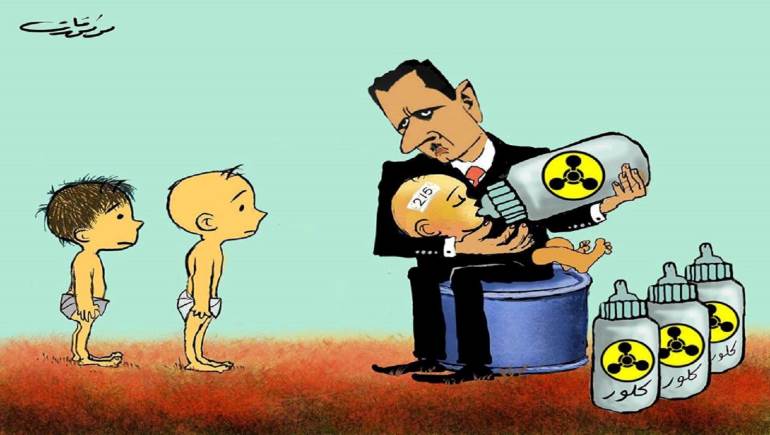

There is now, at last, conclusive evidence that Bashar al-Assad and the Islamic State (ISIS) have used chemical weapons in Syria,

This happened nearly 2.5 years after I collected evidence that proved that Assad had dropped chlorine barrel bombs on the towns of Kafr Zita and Talmenes in Idlib province.

The much anticipated and now leaked report by the United Nations and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) Joint Investigation Mechanism (JIM) has at last concluded that both the Assad regime and ISIL have used chemical weapons on a number of occasions.

The report also states that it is highly likely that Assad still possesses chemical weapons. I in no way blame the OPCW and the JIM for the time taken to confirm our results, because, in effect, they had to follow antiquated and inappropriate rules which, though good for the Cold War, are sub-optimal in the fast-moving asymmetric battlefield of the 21st century.

With the use of chemical weapons appearing to become the “norm”, certainly in Syria and Iraq, these procedures need to be given the flexibility to become effective and, most importantly, timely in the future to deter the use of chemical weapons.

Assad has always used chemical weapons when he has been in dire straits, and to the very good effect: The sarin attack at Ghouta, which killed up to 1,500, saved the regime on August 21, 2013. The use of chlorine barrel bombs on ISIL, which was then attacking Deir Ezzor, saved a strategic military airbase on December 7, 2014. And most recently, on August 11, chlorine gas was dropped on the civilians in Aleppo who looked like breaking the two-year siege.

So it is no surprise that the regime held back up to 200 tons of chemical weapons from the UN/OPCW effort to take down the Assad chemical weapons program.

It should also be no surprise that ISIL is now using chemical weapons with increasing frequency against Peshmerga forces who are closing in on the last and main ISIL stronghold in Iraq, Mosul. ISIL has learned from Assad what a brilliant defensive weapon chemicals can be.

Decisive action needed

So what? No doubt at the UN Security Council on August 30 there will be great platitudes about how terrible this is, and that at some stage Assad will, of course, have his day in the International Criminal Court. But there is no place here for ISIL, certainly under current rules.

And doubtless talk of sanctions. What we need is demonstrative action: A no-fly zone for helicopters preventing them from flying over civilian areas will stop the use of chlorine barrel bombs described in the report forthwith.

It would also stop the illegal use of napalm and high-explosive barrel bombs, which have killed thousands of innocent civilians over the past five years.

Slow-moving helicopters will be easy targets for the international coalition air campaign to track and shoot down if they drop barrel bombs on civilians.

Equally, military ships in the Eastern Mediterranean have the capability to track and intercept helicopters with surface-to-air missiles.

The “bear” in the room is, of course, Russia. But the Russians claim they do not target civilians and certainly would not use banned chemical weapons, so I see absolutely no grounds to veto this proposal in the UNSC. To do so would be completely reprehensible and morally bankrupt.

If the UNSC agrees on a scheme like this on August 30, it could be in place in a matter of hours. Even over the last weekend, we heard of many more innocent civilians being killed by Assad’s barrel bombs.

Read more: Turkey, France to sue Assad regime for chemical massacres in Syria

The situation in Iraq

In Iraq, the Peshmerga should be given every support, including countering chemical attacks in their fight against ISIL, otherwise, they might stop fighting, and we might have to put British, American and other coalition forces, including Middle Eastern countries’, “boots on the ground” to finish the job.

I was in northern Iraq last week training the Peshmerga against the use of chemical weapons, and they seriously lack key equipment. The Black Tigers, a force of 44,000, stationed between Kirkuk and Mosul – and in the forefront of the battle for Mosul – have been subject to at least 12 mustard and chlorine gas attacks in the past 12 months.

One I witnessed in person near Gwer in April 2016. This force has about 2,000 gas masks for the entire force. Their commander, General Sirwan Barzani, told me last week: “I know bombs and bullets are more dangerous but gas terrifies my men.”

All Iraqi Kurds know about “gas” from Halabja when 5,000 died in a single day from the deadly nerve agent sarin, and the Anfal campaign in the 1980s, in which Saddam Hussein allegedly killed 200,000 Iraqi Kurds using chemical weapons.

The UNSC and the international community hasn’t hitherto dealt with the chemical weapon issue well, but now has a chance to be bold and prevent these dreadful weapons becoming the norm in future.

A helicopter no-fly zone in Syria will save hundreds of lives a week, and more support for the Peshmerga will allow them to kick ISIL out of Mosul, and thence Iraq.

Hamish de Bretton-Gordon – Al-Jazeera

Hamish de Bretton-Gordon is a chemical weapons adviser to NGOs working in Syria and Iraq. He is a former commanding officer of the UK Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) Regiment and NATO’s Rapid Reaction CBRN Battalion.